Despite having a stable release model and cadence since December 2003, Linux kernel version numbers seem to baffle and confuse those that run across them, causing numerous groups to mistakenly make versioning statements that are flat out false. So let’s go into how this all works in detail.

This is a post in the series about the Linux kernel CVE release process:

- Linux kernel versions, how the Linux kernel releases are numbered (this post)

- Tracking kernel commits across branches, how to keep track of Linux kernel commits as they move from the main release branch into the different stable releases in an automated way.

- Linux kernel security work how the Linux kernel security team works to fix reported security bugs.

- Linux CVE assignment process, how the Linux CVE team processes bugs and classifies them as CVEs.

- Linux CVE tools, how a kernel commit is turned into a CVE entry automatically and kept up to date over time (future post).

“Old” kernel version scheme is no more

I’m going to ignore the “old” versioning scheme of Linux that was in place before the 2.6.0 release happened on December 17, 2003, as that model is no longer happening. It only confuses people when attempting to talk about code that is over 23 years old, and no one should be using those releases anymore, hopefully. The only thing that matters today about the releases that happened between 1991 and 2003 is that the developers have learned from their past mistakes and now are following a sane and simple release model and cadence.

Luckily even Wikipedia glosses over some of the mess that happened in those old development cycles, so the less said about them, the better. Moving on to…

Kernel version numbers

The only things needed to remember about Linux kernel releases is:

- All releases are “stable” and backwards compatible for userspace programs to all previous kernel releases.

- Higher major and minor version numbers mean a newer release, and do not describe anything else.

All releases are stable

Once the 2.6.0 kernel was released, it was decided that the rule of kernel releases would be that every release would be “stable”. No kernel release should ever break any existing user’s code or workflow. Any regressions that happened would always be prioritized over new features, making it so that no user would ever have a reason to want to remain at an older kernel version.

This is essential when it comes to security bugs, as if all releases are stable, and will not break, then there is both no need to maintain older kernel versions as well as no risk for a user to upgrade to a new release with all bugfixes.

Higher numbers means newer

Along with every release being stable, the kernel developers at the 2.6.0 time decided to switch to a “time based release schedule”. This means that the kernel is released based on what is submitted for any specific development cycle during the 2 week merge window as described in the kernel documentation.

So with a time based releases happening on average every 10 weeks, the only way to distinguish between releases is the version number, which is incremented at each release.

Stable kernel branches

Once the kernel developers started on this “every release is stable” process, they soon realized that during the 10 week development cycle, there was a need to get bugfixes that went into that kernel into the “last” release as that is what users were relying on. To accomplish this, the goal of a “stable kernel release” happened. The stable releases would take the bugfixes that went into the current development tree, and apply them to the previous stable release and do a new release that users could then use.

The rules of what is acceptable into a stable kernel are documented with the most important rule being the first one “It or an equivalent fix must already exist in Linux mainline (upstream).”

Major.Minor.Stable

Kernel version numbers are split into 3 fields, major, minor, and stable, separated by a ‘.’ character. The minor number is incremented by Linus every release that he makes, while the major number is only incremented every few years when the minor number gets too large for people. The major.minor pair is considered the “kernel branch” number for a release, and the stable number is then incremented for every stable release on that branch.

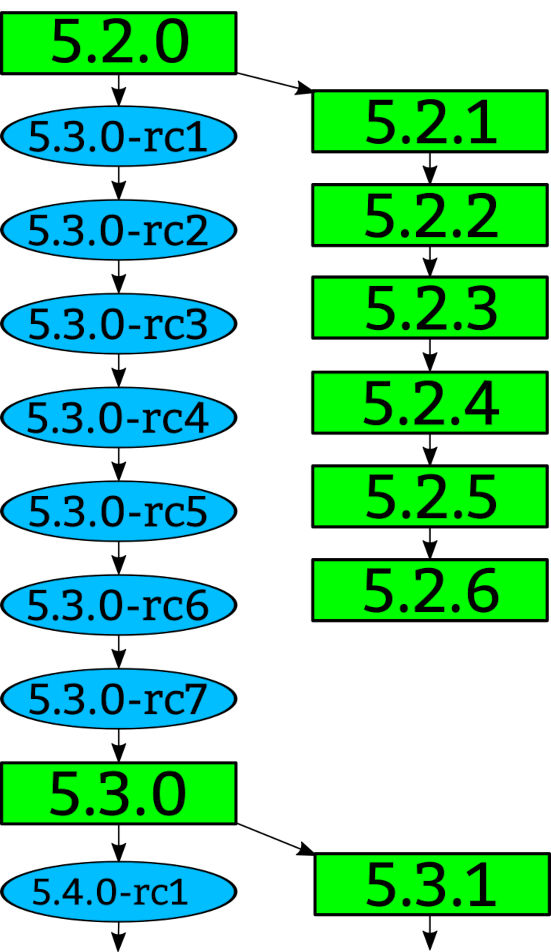

An example makes this a bit simpler to understand. Here is how the 5.2 kernel

releases happened:

First 5.2.0 was released by Linus, and then he continued on with the 5.3 development cycle, first releasing -rc1, and then -rc2, and so on until -rc7 which was followed by a stable release, 5.3.0.

At the time 5.2.0 was released, it was branched in the Linux stable git tree by the stable kernel maintainers, and stable releases started happening, 5.2.1, 5.2.2, 5.2.3, and so on. The changes in these stable releases were all first in Linus’s tree, before they were allowed to be in a stable release, ensuring that when a user upgrades from 5.2 to 5.3, they will not have any regressions of bugfixes that might have only gone into the 5.2.stable releases.

.y terminology

Many times, kernel developers will discuss a kernel branch as being “5.4.y” with “.y” being a way to refer to the stable kernel branch for the 5.4 release. This is also how the branches are named in the Linux stable git tree, which is where the terminology came from.

Stable release branches “stop”

What is important to remember is that stable release branches are ended after a period of time. Normally they last until a few weeks after the next minor release happens, but one kernel branch a year is picked to be a “longterm” kernel release branch that will live for at least 2 years. This kernel is usually the “last” kernel release of the year, and the support cycle can be seen on the kernel.org releases page

This ability for kernel releases to continue for a short while, or many years before going end-of-life, is important to realize when attempting to track security bugs and fixes over time, as many companies get confused when trying to compare version numbers against each other. It is NOT safe to do a simple “if this version number is bigger than the previous one, then all fixes for it will be in the next release.” You have to treat each kernel “branch” as a unique tree, and not compare them against each other in order to be able to properly track changes over time. But more about that later on…